I made a throwaway comment on social media the other day, how I believed that all zombie fiction is essentially the Apollonian and Dionysian dichotomy writ large. Having pondered on the idea for a day or two, I thought it worth expanding upon.

“The Apollonian is based on individuality, and the human form which is used to represent the individual and make one being distinct from all the others. It celebrates human creativity through reason and logical thinking. By contrast, the Dionysian is based on chaos and appeals to the emotions and instincts. Rather than being individual, the barriers on individuality are broken down and beings submerge themselves in one whole.”

(from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollonian)

Now, if that doesn’t sum up the rugged individuals resisting the mindless zombie hordes, I don’t know what does. Broken down to its purest theme, the modern zombie narrative tells us about the struggle of the Apollonian holdouts, maintaining reason and logic against the overwhelming default state of chaos.

Throughout western literature, this idea has been used over and over, by everyone from Nietzsche to Stephen King. As far as the Greeks themselves are concerned, this dichotomy is probably a carry over from earlier Egyptian mythology (which is all about Order resisting Chaos) and seems to be a story as old as recorded history.

In George Romero’s excellent movie Land of the Dead, we see the complete destruction of one man’s Apollonian order, and as the dust settles, an uneasy accomodation between these two philosophies (the survivors of Fiddler’s Green and the evolving zombies). It should be noted that “the Greeks did not consider the two gods to be opposites or rivals, although often the two deities were interlacing by nature.”

In my favourite moment of this movie, the turncoat human Cholo DeMora (played by John Leguizamo) cops an infected bite. He is from that moment on doomed to turn into a zombie, and walk the earth in undeath. Even as his companion offers to end his life (and spare him from this fate) Cholo stops him.

Foxy: [Cholo is bitten by a zombie and Foxy hold a gun aimed at him] It’s your call man.

Cholo: [hesitates then shakes his head no] Nah, I always wanted to see how the other half lives.

And just like that, we realise that Cholo was a Dionysian figure all along. Rebuffed earlier by his employer, this character opens the floodgates to chaos, turning against his own kind, and dooming Fiddler’s Green. Stealing the ultimate weapon, he is ostensibly holding this gated community to ransom for what is effectively useless currency – there is nothing left to the United States but barter economies, walled enclaves in a new Dark Ages. This always bugged me about this movie, but I finally understand that it was never about the money for Cholo. This is the story of an Apollonian figure rejecting his Dionysian counterpart, who then behaves true to form.

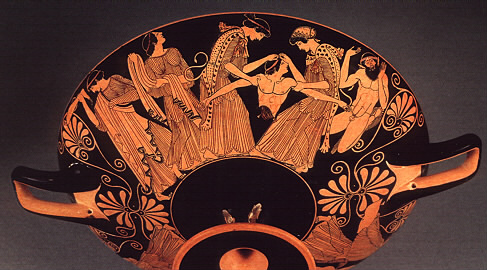

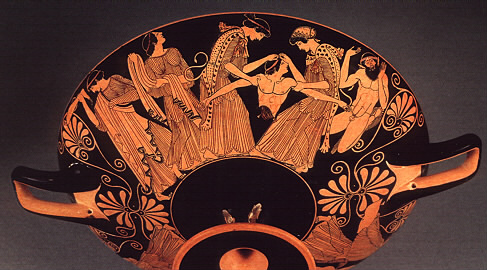

Finally, I’d like to really draw a long bow, and talk about the Maenads. These were the female followers of Dionysius, known for madness and chaos, for drunken revelries in the wilderness. In every story they are mindless, wild, individual creatures broken down and remade as agents of chaos – a mad group, never individuals from that point.

It’s almost incidental that they throw the equivalent of wild parties, with drinking, mad dancing and crazy music. Discount these facts, and everything else points to the ancient Greeks inventing the modern zombie some 2000 years before Romero thought of it.

“Rather than being individual, the barriers on individuality are broken down and beings submerge themselves in one whole.”

In the maenads, we have women who reject their role, murdering their own children, turning from civilisation. Anytime they encounter man or beast, they attack it in a frenzy, tearing it limb from limb. Whenever they eat flesh, it’s not for sustenance, but in an attempt to consume the divine, to rise above their earthly forms. Much like the zombies, they aren’t eating to survive. It’s a communion, a frenzy that exists beyond the normal actions of life.

“Ack. I should have aimed all my javelins for the head.”

“The goal was to achieve a state of enthusiasm in which the celebrants’ souls were temporarily freed from their earthly bodies and were able to commune with Bacchus/Dionysus and gain a glimpse of and a preparation for what they would someday experience in eternity. The rite climaxed in a performance of frenzied feats of strength and madness, such as uprooting trees, tearing a bull (the symbol of Dionysus) apart with their bare hands, an act called sparagmos, and eating its flesh raw, an act called omophagia. This latter rite was a sacrament akin to communion in which the participants assumed the strength and character of the god by symbolically eating the raw flesh and drinking the blood of his symbolic incarnation. Having symbolically eaten his body and drunk his blood, the celebrants became possessed by Dionysus.”

(from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maenad)

So, in summary, whenever we tell a zombie story, we’re reverting to a very old mythology. If we do it properly, we’re exploring the Apollonian-Dionysian dichotomy each and every time.